The Harbour Landscape of Taposiris Magna (Egypt) – 2022-Ongoing

Bérangère Redon

Image (c) MATJAZ KACICNIK

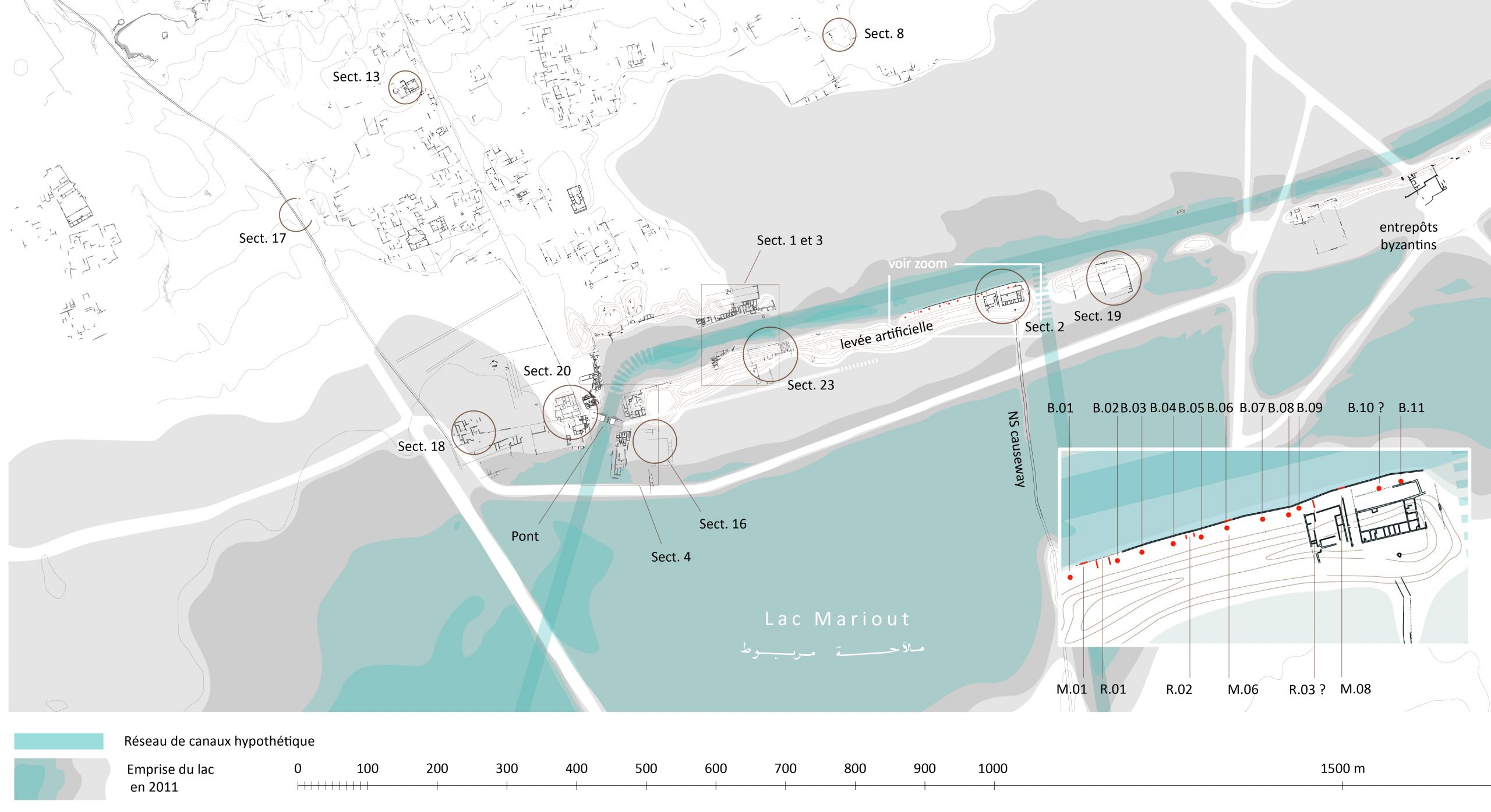

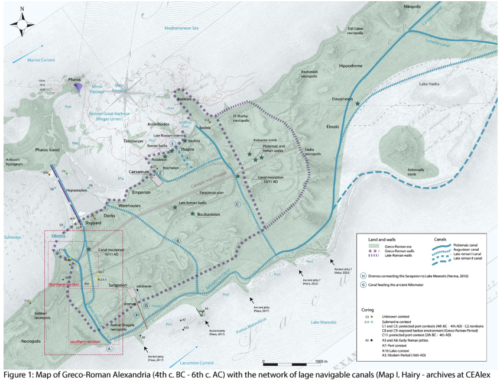

The city of Taposiris Magna developed from the 3rd c. BC onwards on the taenia, a ridge which separates the Mediterranean Sea from its hinterland. Extending on more than 30 ha, the site, occupied until the early 8th c. AD, owes its prosperity to its location, 45 km west of Alexandria, in Mareotis. Designated as the western gateway to Egypt by Emperor Claudius, it is the hub of a vast port system in Mariut basin. Its harbour –partially immersed by the lake Mariut– is together with that of Marea, one of the two major port complexes west of Alexandria.

The French archaeological mission launched in 1998 is the first to undertake a sustained investigation of Taposiris’ harbour. By crossing archaeological soundings and integrated paleoenvironnemental study it challenged previous theories and demonstrated that the port complex was artificially dug in marshy areas in the 2nd c. AD, linked to a long canal forming an artery from Marea to the western border. A major reconfiguration took place at the end of the Byzantine period with the construction of warehouses and public buildings. They testify to a great development for Taposiris between the 6th and 8th c., linked to its function as port city, and connected to a series of settlements along the shores west of Alexandria.

The new hypotheses on the origin and functioning of the port, and the importance of its Byzantine phase, made it necessary to carry out an extensive archaeological campaign in the western part of the port, where numerous facilities and administrative buildings have been surveyed but never explored. The aim was to identify phase by phase, from its development in the Roman period to its abandonment, what the port landscape looked like in relation to environmental changes and link its evolution to urban history.

Read more on the project website.

In 2022, the excavations carried out to the west of the Roman bridge of Taposiris Magna revealed the existence of an urban district bringing together several public buildings erected in the 7th c. AD. One of them, well preserved, presents characteristics of a public building : monumental staircase and paved rooms with benches and colonnade. The nature of these buildings remains to be determined, but it is tempting to associate them with administrative/economic activities linked to the harbour system renewed during the Byzantine and Islamic transition. These buildings also present rapid successive modifications (transformation of spaces and internal communications, raising of floors), which shows the interest given to this district at this period. It highlights the intensity of the activities in an area that is definitely strategic, between the port canal and the city. These elements offer an interesting study case on the organisation of a lake harbour the during the Byzantine and Islamic transition.

Extensive work on the EW levee and the public buildings to the north of the Roman bridge was essential for understanding the history of the area on the longue durée. It was also urgent for two reasons:

- The artificial rise in the lake’s water level, linked to government programmes, had caused whole sections of the northern slope of the artificial EW levee to collapse.

- The Sahel Road development, part of the government’s policy of major works in both the southern and the northern bank of the Mariut lake, has resulted in the destruction of the eastern tip of the EW levee and the eastern jetty at Taposiris, the deterioration of several sites further east, one of which, Gamal, has been almost completely destroyed.

As a result our main objectives in 2023 were as follows:

- To define the functions of the complex building in sector 20 (‘New Building’), close to the Roman bridge and along the main NS road. Its monumental character and an ostracon found in 2022 (read by J.-L. Fournet, Collège de France) suggested that it had a public and commercial function.

- To investigate the extent and chronology of the remains uncovered on the levee, which had collapsed in whole sections on its northern flank as a result of rising water levels.

To achieve these objectives we have focused our work on these two areas (fig. 1).

- A new sector was investigated in 2023 on the artificial east-west levee (sector 23) (fig. 2). Washed by the rising water levels and collapse of the land, a number of structures (portico, warehouse, series of mooring bollards) had been exposed. We excavated and did an architectural survey of three areas, as well as a cleaning-up of the north bank as far as sector 2, depending on the architectural remains visible.

- The excavations in the “New Building” (sector 20) were resumed. They uncovered new rooms mainly to the south, confirming the extent of the building as forecast in 2022 (1000 m²). A small trench was dug to the south between the New Building and the South Building, in what appears to be an alleyway, to establish what type of link (chronological, functional) unites them or not, but this will have to be extended in 2024 to reach any real conclusions.

In sector 23, two successively erected Roman buildings line the canal bank and were quickly abandoned in the late 2nd-early 3rd century. The first is a monumental portico 58 m long with doric columns, and shortly afterwards, a warehouse with 49 pillars covering an area of around 405 m². Stratigraphy proves that there was no levee during the Early Roman period, just a canal. Later in the early 3rd c., the levee was erected, and then raised. This shows a rapid succession of phases and more complex developments than we had previously thought.

Towards the east, a series of 11 mooring bollards and at least one ramp were installed all along the northern slope of the levee. Exceptionally well preserved, they illustrate how the port system functioned, probably at the very time when the warehouses in sector 2 were being built. These monuments make it possible to define the boundary of the canal on this section of the levee, while its course remains hypothetical everywhere else.

The campaign in the “New building” (sector 20) was decisive for our knowledge of its last two phases. From at least the 2nd quarter of the 7th century onwards, the building covered an area of more than 1000 m² and had one storey accessed by a staircase. Its public nature has been confirmed by the identification of receipts on ostraca. Sporadic redevelopment illustrates the final opportunistic reoccupation in the mid 7th c.

The project work could not have been completed without the efforts of the entirely team, notably:

– Joachim Le Bomin, co-director of the mission

– Marie-Françoise Boussac, historian and previous director of the mission

– Lyubomir Malinov, archaeologist

– Julie Marchand, ceramologist

– Pauline Piraud-Fournet, architect

– Alexandre Rabot, geomatician

The aims for 2025 are based on the results obtained during previous campaigns which documented the Roman and Byzantine port infrastructures as part of the forthcoming monographic publication; they also identified more precisely the last phase of the site and the reasons for its abandonment (economic, political, environmental factors) towards the end of the 7th-early 8th c. AD after the Persian and Arab-Muslim invasions.

The Roman harbour system is now better understood, with the discovery under the artificial levee of 2nd and 3rd c. warehouses (one 58 m long with a portico, the other with more than 30 pillars) and mooring bollards along the canal. Our work has also shown that a global reconstruction of the port infrastructures was carried out in the mid 7th c. alongside that of the town. To the west of the bridge, exploration of an area dedicated to port activities uncovered a huge building with a monumental staircase and colonnaded rooms of a possible public and/or administrative nature. A new excavation area opened in the heart of the Byzantine city in a vast residential area contemporary with the harbour, has raised the question of the interactions between the port and the city.

The objectives for 2025 are thus:

(1) To better understand the organization of the Byzantine-Umayyad port: the excavation will focus on the remains that are still above water to the west of the bridge (sector 20). Operations will be extended in the future to the northern part of the port, where there are contemporary buildings.

(2) To link port and urban history: work will continue in the residential area (sector 12), which contains well-preserved buildings that have never been explored.

(3) To insert the end of Taposiris in a regional context: the site has many similarities with Marea/Philoxénité, which survived as a more dispersed settlement until the middle of the 8th c. A comparative study would focus on chronology, variations in urban density and impact of politico-economic factors.

SPACE